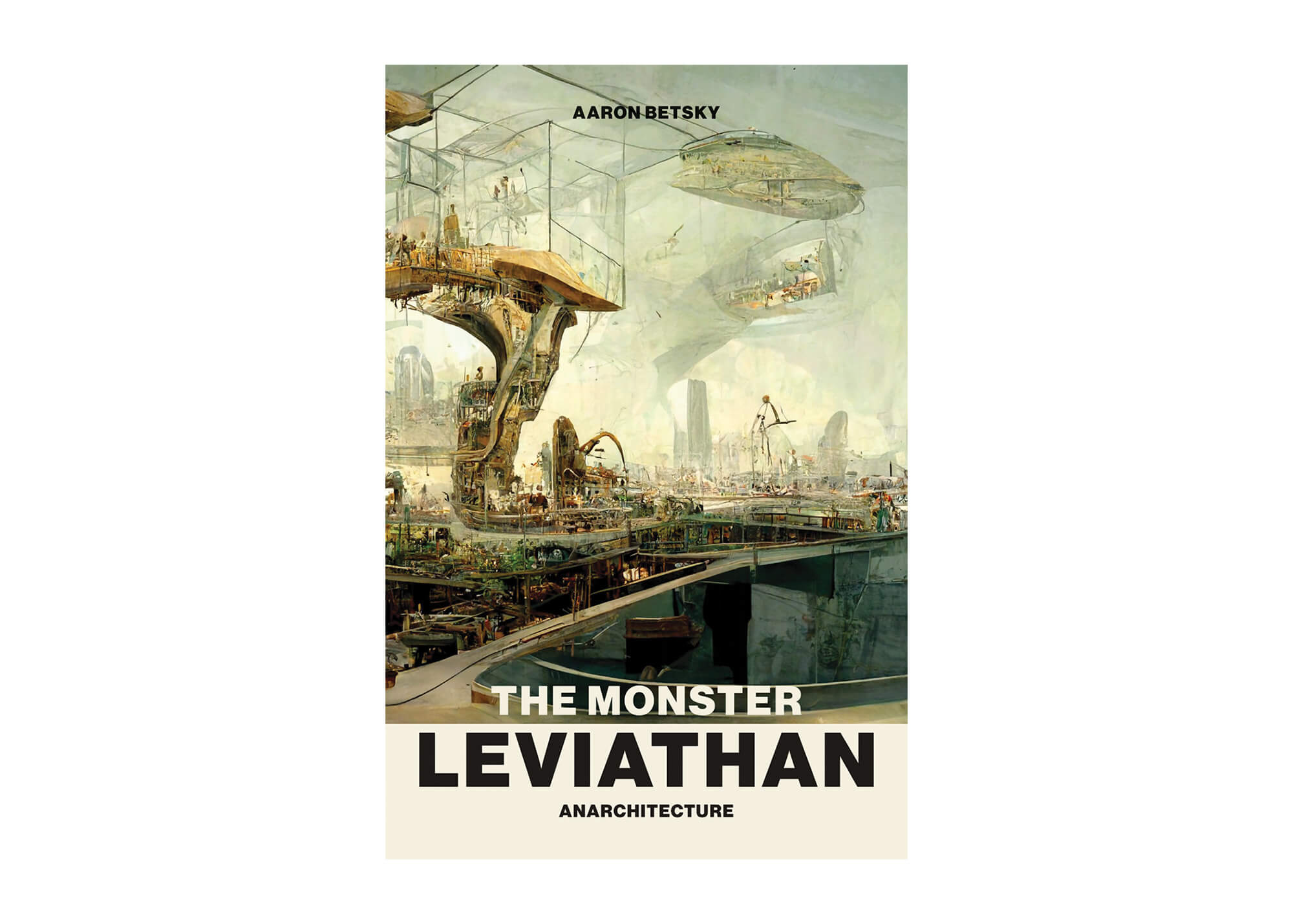

The Monster Leviathan | Aaron Betsky | The MIT Press | $44.95

“‘Hillbillies and bellies, poor excuses for shepherds:

We know how to tell many believable lies,

But also, when we want to, how to speak the plain truth.’

So spoke the daughters of great Zeus . . . they breathed into me

A voice divine, so I might celebrate past and future.

And they told me to hymn the generation of the eternal gods,

But always to sing of themselves, the Muses, first and last.”

—Hesiod, Theogony (27–35), trans. Stanley Lombardo

With The Monster Leviathan: Anarchitecture, critic and theorist Aaron Betsky offers a sweeping survey of those oneiric, visionary, and vanguard works that haunt contemporary architecture and, more emphatically, of the ideas and theories that illuminate them.

Betsky takes his title from Frank Lloyd Wright’s portrayal of the modern city as a quasisentient beast, part living monster, part churning machine, in “The Art and Craft of the Machine,” a 1901 lecture in which the architect traded his polemical certainty about the future of the American metropolis for poetic ambivalence about humanity’s place within it. Drawing on Wright’s vivid imagery, his own shocking encounter with the work of Archigram as a young boy, and borrowing the term from Gordon Matta-Clark, Betsky develops a theory of “anarchitecture,” an other architecture comprised of “forms and images . . . that might be out there, in time and place uncertain, and that might serve as analogies for our own.” Such works, he claims, avoid the twin traps of utopian naivete and dystopian cynicism to suggest instead ambivalent futures that are “just believable enough to convince us, and just fantastical enough to open our eyes.” In this, Betsky delivers more than just a primer on the history of the avant-garde and a survey of the theoretical foundations of visionary design. He also outlines a manifesto for an architecture that operates less like conventional built form than like fine art, music, or literature, and whose efficacy obtains most forcefully in a conceptual realm beyond buildings.

Across an introductory chapter and nine thematic sections, Betsky finds hints of anarchitecture in a dizzying array of architectural projects organized in relation to a who’s who of major philosophers, theorists, and critics of the 20th and 21st centuries. He examines the “explosion” of Italian futurism and Russian constructivism through the writing of Filippo Tommaso Marinetti; the deceptive “veil” that occludes the reality of modern technology through the philosophy of Martin Heidegger; the “empty signs” of Archigram, Peter Eisenman, and Aldo Rossi through the Marxist critique of Manfredo Tafuri; the “implosion” of meaning in the work of Zaha Hadid, Bernard Tschumi, and Lebbeus Woods through Jacques Derrida’s deconstruction; and the “smooth and striated” early work of Diller and Scofidio through the theories of Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari. Major figures including Rem Koolhaas, Robert Venturi, and Wright provide both theoretical provocation and architectural propositions in three chapters that focus primarily on their work, while two closing chapters address recent contributions by Black, queer, and feminist architects and theorists and a set of recent digitally savvy designer/thinkers, most of them junior faculty at academic institutions across the United States. Throughout, fellow travelers and like-minded voices from architecture and adjacent fields slip in and out of frame to add depth—and more than a few surprises—to a star-studded ensemble cast.

To hold this congeries of recent, not-so-recent, and contemporary architectural thought together, Betsky draws inspiration from Greek mythology and its use of the aorist tense, a grammatical feature of Ancient Greek that loosens the link between a verb’s action and the passage of time. The aorist, which has no direct analog in English, increases the ability of past events to slide across centuries as it imparts an air of conviction to even the most fantastical constructions. Thus, in Hesiod’s phrasing, “Zeus Aegisholder and his lady Hera” are then, now, and forever “in gold sandals striding;” “earthquaking” Poseidon stirs calamity for our ancestors, our offspring, and ourselves; and “Aphrodite, eyelashes curling,” basks for eternity in immortal pulchritude.

With mythological imagery in mind, Betsky mostly dispenses with the tedious i-dotting and t-crossing that can mar more conventional histories and instead montages ideas and images into a personal cosmology of the immediate present. His ambitious scope sometimes has him moving through architectural examples rather quickly. Theorists provide the main narrative thread for each chapter. These he presents with impressive erudition, working primarily by seeking similarities in his subject matter. In one chapter, he brings Deleuze and Guattari into alignment with the philosophers Graham Harman and Timothy Morton and then, in an unexpected leap, with the urban speculations of Lars Lerup. In another, he unpacks Koolhaas’s paranoid-critical readings of Berlin, London, and Manhattan, then follows their implications into the data-driven work of younger Dutch firms MVRDV and UN Studio and on to theorist Benjamin Bratton’s ruminations on planetary-scaled datascapes in his 2016 tome, The Stack.

These elisions bring both benefits and costs. Students and general readers will find a solid, wide-ranging, and well-illustrated account of the last 150 years of speculative architecture, though some may blanch at the surfeit of long block quotes and nearly 500 pages that would have benefited from a firmer editorial hand. Throughout, Betsky provides clear and accessible glosses of sometimes painfully dense primary sources that will serve neophytes and veterans alike, though more experienced mythologists may, on occasion, want to raise an index finger and say things like, “Hold on, Aaron! Doesn’t Harman more often oppose Deleuze and Guattari than agree with them?” or frown at such generalizations as, “Lefebvre, Soja, Sloterdijk, and Foucault all seek for something that is by its very nature elusive.”

Of course, all theories work by distilling general principles from specific examples, and as the sociologist Murray Davis pointed out in a classic essay, they accrue value not because they are true, but because they are interesting. With his version of anarchitecture, Betsky has crafted a uniquely interesting and valuable theory that has less to do with nailing down facts than with reminding readers to pay attention to those glimpses of possibility that flicker the edge of perception, where what we take for reality mingles with our imagination.

In this, The Monster Leviathan has much in common with the ancient myths Betsky studied in his youth in the Netherlands. Indeed, readers could do worse than to approach this book as a personal odyssey across the wine-dark sea of contemporary architecture in which our hero, owl-eyed Aaron, matches wits with a seemingly endless array of fantastical beasts and curious creatures. The author suggests as much at the outset, but for my money, with its deference to the “believable lies” and occasional “plain truth” of critical theory and philosophy, Betsky’s book resonates less with Homer’s Odyssey than with Hesiod’s Theogony, which presents a thorough (if contestable) genealogy of the gods the Greeks revered and begins and ends with the nine Muses (including Thalia, goddess of architecture, agriculture, and comedy). Like these sirenic voices, the famous thinkers that propel Betsky’s narrative continue to “bestow song that beguiles” upon generations of architects—and at least one Dutch shepherd from Montana—who tell “what is, what will be, and what has been.”

Todd Gannon is a professor of architecture at The Ohio State University’s Knowlton School. His most recent book is Figments of the Architectural Imagination.