NASA

Regardless of the outcome of this year’s election, the United States will have a new president in a few months. Although there are myriad issues of greater importance than spaceflight to most Americans, a new leader of the country will inevitably take a fresh look at the nation’s space policy.

Among the highest priorities for the next administration should be shoring up NASA’s Artemis plan to return humans to the Moon. This ambitious and important program is now half a decade old, and while the overall aims remain well supported in Congress and the space community, there are some worrying cracks in the foundation.

These issues include:

- The first crewed flight on the Orion spacecraft, a vehicle that has been in development for two decades, remains in doubt due to concerns with the heat shield.

- The first lunar landing mission has no reliable date. Officially, NASA plans to send this Artemis III mission to the Moon in September 2026. Unofficially? Get real. Not only must Orion’s heat shield issue be resolved, but it’s unlikely that both a lunar lander (SpaceX’s Starship vehicle) and spacesuits (built by Axiom Space) will be ready by this time. The year 2028 is probably a realistic no-earlier-than date.

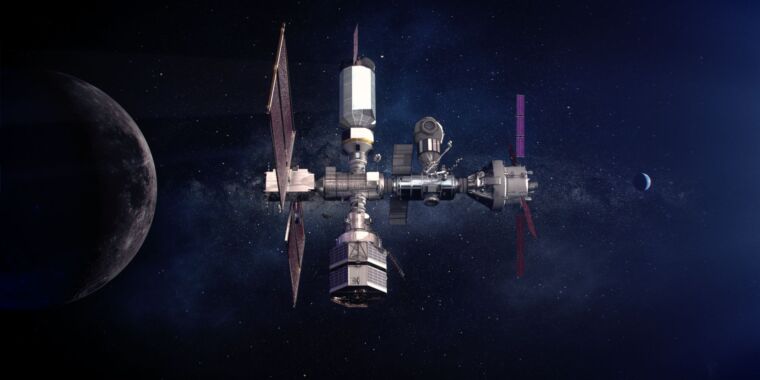

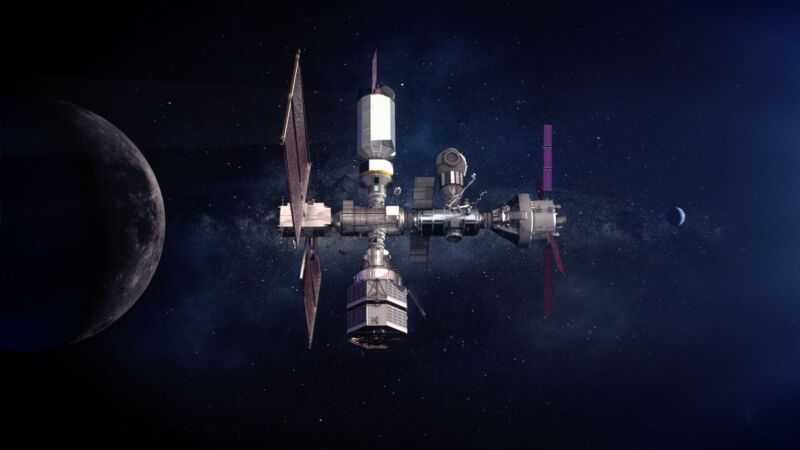

- The space agency’s plans after Artemis III are even more complex. The Artemis IV mission will nominally involve the debut of a larger version of NASA’s Space Launch System (SLS) rocket, a new launch tower, and a stopover at a new space station near the Moon, the Lunar Gateway.

- There is increasing evidence that China is pouring resources into a credible lunar program to land two astronauts on the Moon by 2030, seeking a geopolitical “win” by beating America in its return to the Moon.

A flat or even reduced NASA budget compounds all of these issues, and the space agency is unlikely to receive significant increases in the near term. The fundamental problem with Artemis, therefore, is that NASA is trying to do too much with its deep space program with too few resources. We have already seen evidence of NASA cannibalizing its science programs—including significant cuts to the Chandra space telescope and the cancellation of the VIPER mission—to support Artemis’ ballooning costs.

If the agency continues down this path, like a frog in boiling water, the Artemis Program is likely to end in failure.

A simple plan

Fortunately, I have a solution. It may not be politically popular, and there are losers. Among the biggest ones are Boeing, SpaceX, and two NASA field centers, Marshall Space Flight Center and Johnson Space Center. However, if Artemis is to succeed, difficult choices must be made.

For policymakers, there are two strategic aims at risk here. The first is losing the geopolitically important race against China, Russia, and their partners back to the Moon in the 21st century. The second is sacrificing a sustainable lunar program for one that is unaffordable in the long term.

With that context, here are the principal policy choices I believe should be made to shore up the Artemis Program both in the near and long term:

- Cancel the Lunar Gateway

- Cancel the Block 1B upgrade of the SLS rocket

- Designate Centaur V as the new upper stage for the SLS rocket.

That’s it in a nutshell. Read on for the details.