The next year is crucial for the future of NASA and its plans to extend human activity in low-Earth orbit. For the first time in decades, the US space agency faces the not-too-distant prospect of failing to have at least one crew member spinning around the planet.

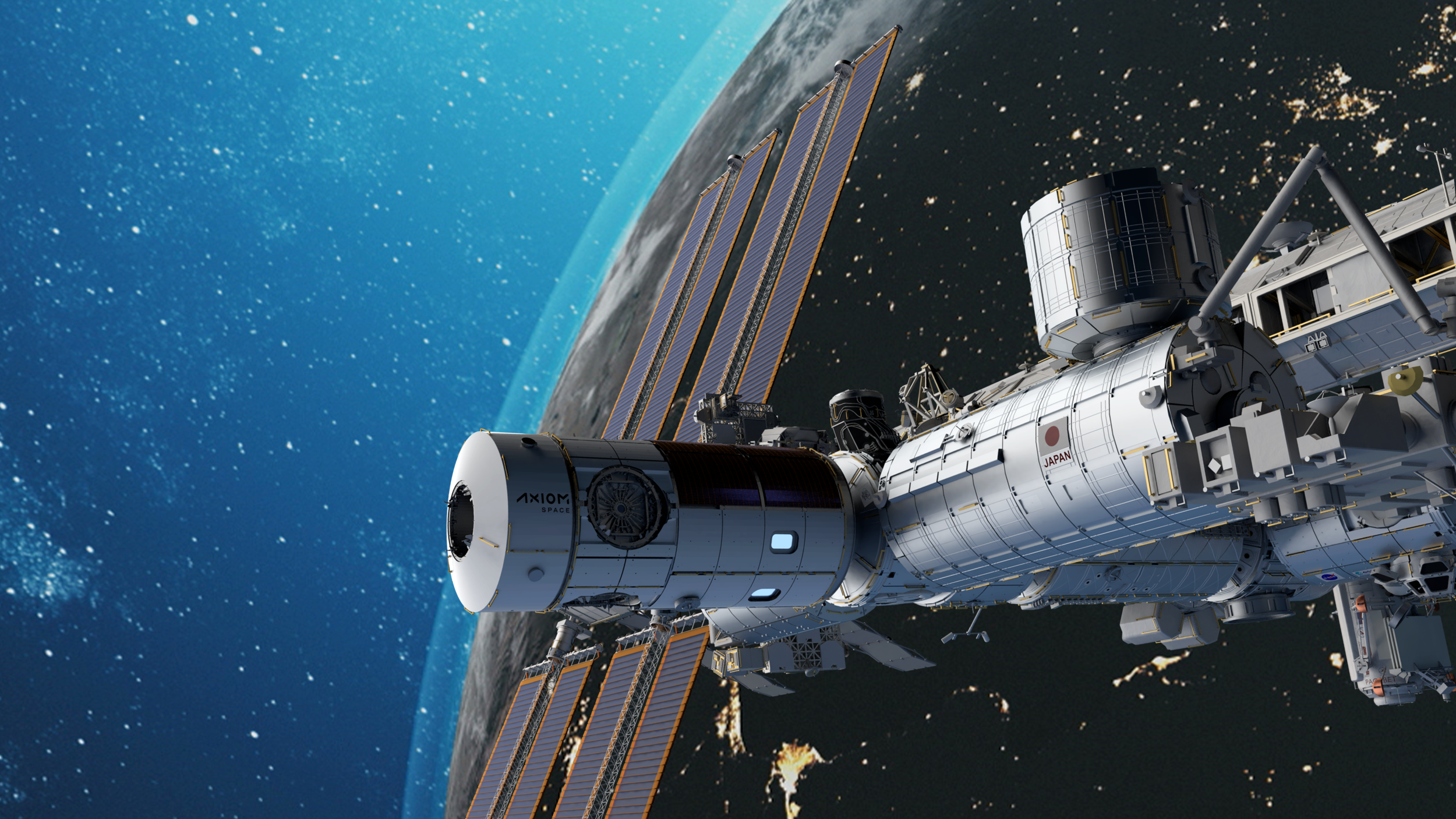

Over the next several months, NASA will finalize a strategy for its operations in low-Earth orbit after 2030. Then, toward the end of next year, the space agency will award contracts to one or more private companies to develop small space stations for which NASA and other space agencies will become customers rather than operators.

But none of this is certain, and as NASA faces a transition from its long-established operations on the International Space Station to something new, there are many questions. Foremost among these is whether NASA really needs to continue having a presence on low-Earth orbit at all, especially as the space agency’s focus turns toward the Moon with its Artemis Program.

Microgravity research remains essential

The answer to that question is definitively yes, said Pam Melroy, the deputy administrator of NASA, in an interview.

“It really is on us to tell our story as well as we can,” she said. “I don’t think people realize the connection between low-Earth orbit to Artemis, and Moon to Mars, and future human exploration. I hope to help people understand better why it’s so important for us to push hard on this.”

In recent years, as NASA has been able to support a crew of four astronauts at a time on the space station, the space agency has started to maximize the scientific potential of the orbiting laboratory. This is not just for basic research in microgravity but for studying the long-term health impacts of humans in space.

“We are so not done with research in microgravity,” Melroy said. “We’ve gotten ourselves to the point where we kind of understand the risks of a one-year duration mission in space, but we’re going to have to keep pressing on that because we really have to get our arms around mitigations and solutions for what will likely be a two- or three-year trip to Mars.”