This June marked two years since the Dobbs ruling effectively overturned national protections for access to abortion as a constitutional right. In that time, we’ve seen 21 states ban abortion or restrict the procedure earlier in pregnancy than the standard set by Roe v. Wade. The architecture industry has remained largely absent on this issue, chalking it up to abortion being seen as too taboo and controversial to engage in directly rather than for seeing it what it is: A health and reproductive care procedure, and an extremely common one at that. One in four people capable of pregnancy in the United States will have had at least one abortion.

As a healthcare architect whose projects have covered the entire care continuum, I know this to be unequivocally true: Abortion access is healthcare.

When I have spoken about the issue of abortion and architecture, certain members of our design community have asked me to replace the word abortion with “something else” or not use it at all. And the AIA’s Academy of Architecture for Health has refused my requests to create a presentation to better educate their members on issues at the intersection of abortion access, the built environment, and state and federal policy.

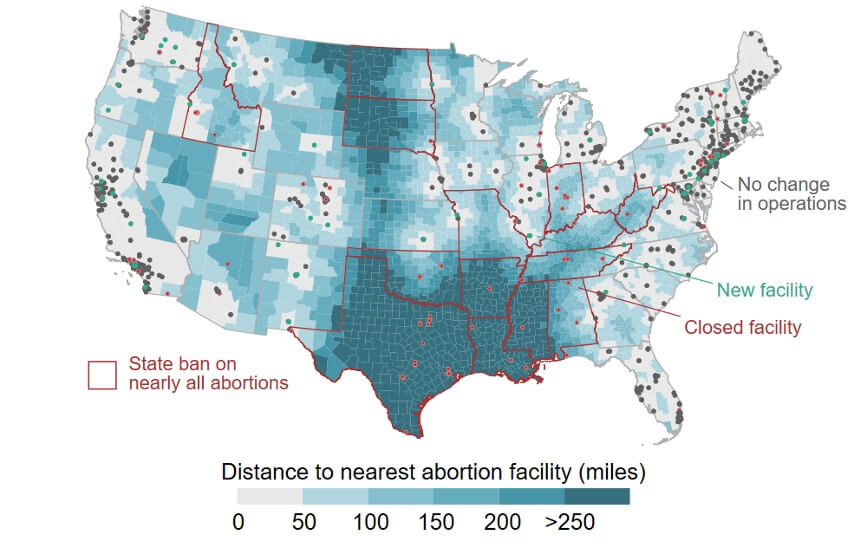

In a profession that is committed to designing spaces that support optimal patient health, safety, and wellbeing, it is our duty to step up and apply our expertise where we can toward that mission without passing value judgements on the services being provided. And it couldn’t be timelier. New reporting points to the toll that stringent restrictions have taken: 171,000 people were forced to travel out of state last year for abortions and there are more and more stories coming out about women’s lives being put on the line trying to find care. Studies show maternal death rates in states that restrict abortion access are 62 percent higher than in states where abortion is more easily accessible.

We’re witnessing what happens where that isn’t industry standard practice and adequate architectural guidance for abortion care facilities. The fewer facilities that are available, the greater people are put at risk. Period. In an election year where all forms of reproductive care and family planning have been put on the table, it has never been more important to have accessible guidelines of standard practice. And just because it’s seen as too complicated to take on is even more reason to address this issue directly rather than shy away.

So, I decided to take it on directly with my peers by submitting an amendment to the Facilities Guidelines Institute’s Guidelines for Design and Construction of Outpatient Facilities upcoming 2026 edition. The Facility Guidelines Institute (FGI) is an organization that develops and publishes some of the most important guidelines for the design and construction of hospitals, outpatient facilities, and residential health, care, and support facilities in the United States. The Institute determines both standard industry practice in healthcare design and state-level code and regulations. Yet, these gold standards have a serious design flaw—the FGI has never provided direct design guidance for abortion clinics and facilities as an example of a reproductive healthcare facility typology.

I explained in my proposal how this addition to the guidelines could prevent clinic closures and improve patient safety by providing better access to abortion care in states where abortion remains legal. Out of the almost 1,800 proposals for amendments submitted, the proposal to directly mention abortion care had more in-favor opinions from the public period commenting process than any other proposal. In addition, the FGI’s Benefit-Cost Committee agreed with the proposal. A member of that committee even publicly commented it was an “important clarification” to include abortion clinics as an example of reproductive healthcare in the revisions. Frustratingly, the FGI’s Health Guidelines Revision Committee (HGRC) still decided to reject the proposal without adequate reason or explanation. I can only speculate on the different reasons why.

I understand that the guidelines normally try to provide design standards based on health-related risks of procedures instead of the actual procedures themselves. To someone unfamiliar with connections between U.S. abortion and care and the built environment, it might have even seemed as though the proposal’s scope began to creep too far into specifics. The wholesale rejection was a clear indication the HGRC committee did not have the necessary reproductive healthcare expertise needed to make an informed decision the subject. If they did, the FGI would have already realized that their inaction to mention the word abortion in their guidelines contributes to anti-abortion lobbyists and state politicians being able to pass building facility requirement TRAP (Targeted Restriction on Abortion Providers) laws more easily.

TRAP laws create burdensome and medically unnecessary regulations on abortion building facility requirements with the goal of forcing abortion facilities to close. It was disappointing to realize that an organization that prides itself on producing the most widely recognized planning and construction guidelines in the healthcare design industry formed a committee that was completely ignorant to the fact that states with TRAP laws subject abortion-providing facilities to different requirements than, for example, other surgeries subject only to outpatient-based surgery (OBS) laws. For example, a study published in the American Journal of Public Health in 2018 found that TRAP laws were more likely than OBS laws to require facility licensing and procedure rooms.

If the HGRC committee had taken the time to properly educate themselves after calling attention to TRAP laws, they may have realized this unusual need for specificity would have advanced the quality of abortion healthcare. Simple language can combat TRAP laws that systematically shutter abortion clinics across the states.

Although the FGI revisions committee rejected the initial proposal to include abortion facilities in their 2026 outpatient guidelines, I believe it is not too late for them to change course this year. Final revisions have not been printed, so I’m encouraging our design community to take this opportunity to suggest the FGI reconsiders the rejection of my proposal going to Contact Us – Facility Guidelines Institute (fgiguidelines.org) There will not be another chance to revise the FGI guidelines until the 2030 Revision cycle. With so much out of control in America today and where the stakes couldn’t be higher, engaging with this issue is one tangible way that architects can make a difference. The time for action is now.

Jordan Kravitz is a healthcare project architect, medical planner, and researcher. She is the author of “A State By State Guide To Understanding Outpatient Abortion Clinics In Relation To Trap Laws And The Built Environment.”