Michael DeMocker/NASA

The NASA program to develop a new upper stage for the Space Launch System rocket is seven years behind schedule and significantly over budget, a new report from the space agency’s inspector general finds. However, beyond these headline numbers, there is also some eye-opening information about the project’s prime contractor, Boeing, and its poor quality control practices.

The new Exploration Upper Stage, a more powerful second stage for the SLS rocket that made its debut in late 2022, is viewed by NASA as a key piece of its Artemis Program to return humans to the Moon. The current plan calls for the use of this new upper stage beginning with the second lunar landing, the Artemis IV mission, currently scheduled for 2028. In NASA parlance, the upgraded version of the SLS rocket is known as Block 1B.

However, for many reasons—including the readiness of lunar landers, Lunar Gateway hardware, a new mobile launch tower, and more—NASA is unlikely to hold that date. Now, based on information in this new report, we can probably add the Exploration Upper Stage to the list.

“We found an array of issues that could hinder SLS Block 1B’s readiness for Artemis IV including Boeing’s inadequate quality management system, escalating costs and schedules, and inadequate visibility into the Block 1B’s projected costs,” states the report, signed by NASA’s deputy inspector general, George A. Scott.

Quality control a concern

There are some surprising details in the report about Boeing’s quality control practices at the Michoud Assembly Facility in southern Louisiana, where the Exploration Upper Stage is being manufactured. Federal observers have issued a striking number of “Corrective Action Requests” to Boeing.

“According to Safety and Mission Assurance officials at NASA and DCMA officials at Michoud, Boeing’s quality control issues are largely caused by its workforce having insufficient aerospace production experience,” the report states. “The lack of a trained and qualified workforce increases the risk that the contractor will continue to manufacture parts and components that do not adhere to NASA requirements and industry standards.”

This lack of a qualified workforce has resulted in significant program delays and increased costs. According to the new report, “unsatisfactory” welding operations resulted in propellant tanks that did not meet specifications, which directly led to a seven-month delay in the program.

NASA’s Inspector General was concerned enough with quality control to recommend that the space agency institute financial penalties for Boeing’s noncompliance. However, in a response to the report, NASA’s deputy associate administrator, Catherine Koerner, declined to do so. “NASA interprets this recommendation to be directing NASA to institute penalties outside the bounds of the contract,” she replied. “There are already authorities in the contract, such as award fee provisions, which enable financial ramifications for noncompliance with quality control standards.”

The lack of enthusiasm by NASA to not penalize Boeing for these issues will not help the perception that the agency treats some of its contractors with kid gloves.

Seven years late

The new report predicts that Block 1B development costs will reach $5.7 billion before it ultimately launches, which is already $700 million more than a cost estimate NASA formally established just last December.

As for the upper stage itself, NASA initially predicted development costs would be $962 million back in 2017. However, the new report predicts that the Exploration Upper Stage will actually cost $2.8 billion, or three times the original cost estimate. (For what it is worth, Ars used a simple estimating tool in 2019 to predict the Exploration Upper Stage development cost would be $2.5 billion. So it’s not like it was a huge secret that NASA and Boeing would blow out the budget here).

NASA Inspector General

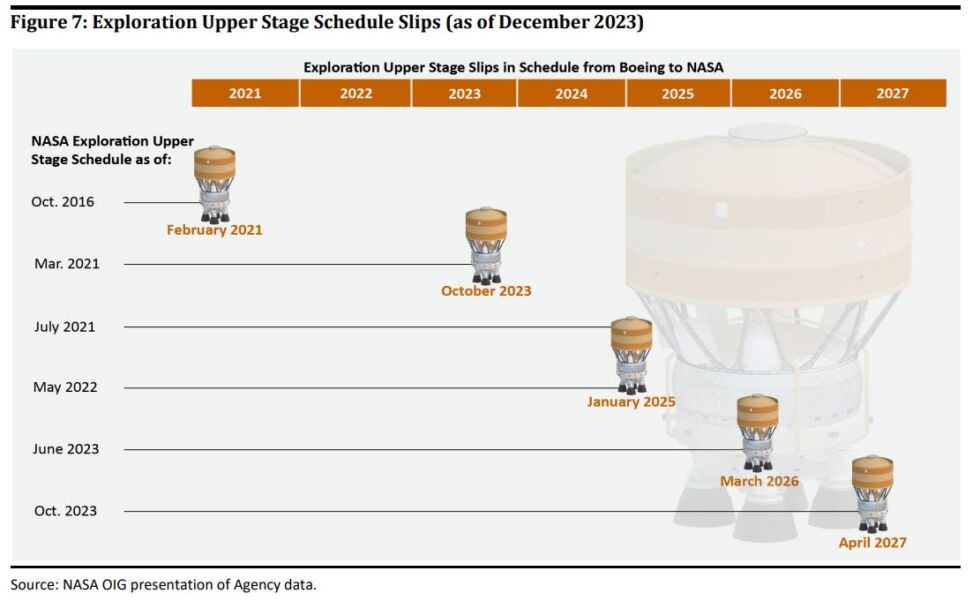

However, the increased costs will benefit Boeing since this is a cost-plus contract that pays for all of Boeing’s expenses, plus a fee. This may help to explain why a development program that was originally supposed to be completed in 2021 is not unlikely to be finished until 2028 at the earliest.

And what for? The Space Launch System works great as it is. There are far, far cheaper upper stages that could be used for the rocket’s primary function to launch the Orion spacecraft to lunar orbit, including United Launch Alliance’s reliable (and ready) Centaur V upper stage. With Starship and New Glenn, NASA will also soon have two very powerful commercial super heavy lift rockets to draw upon.