Lisa Fagin Davis

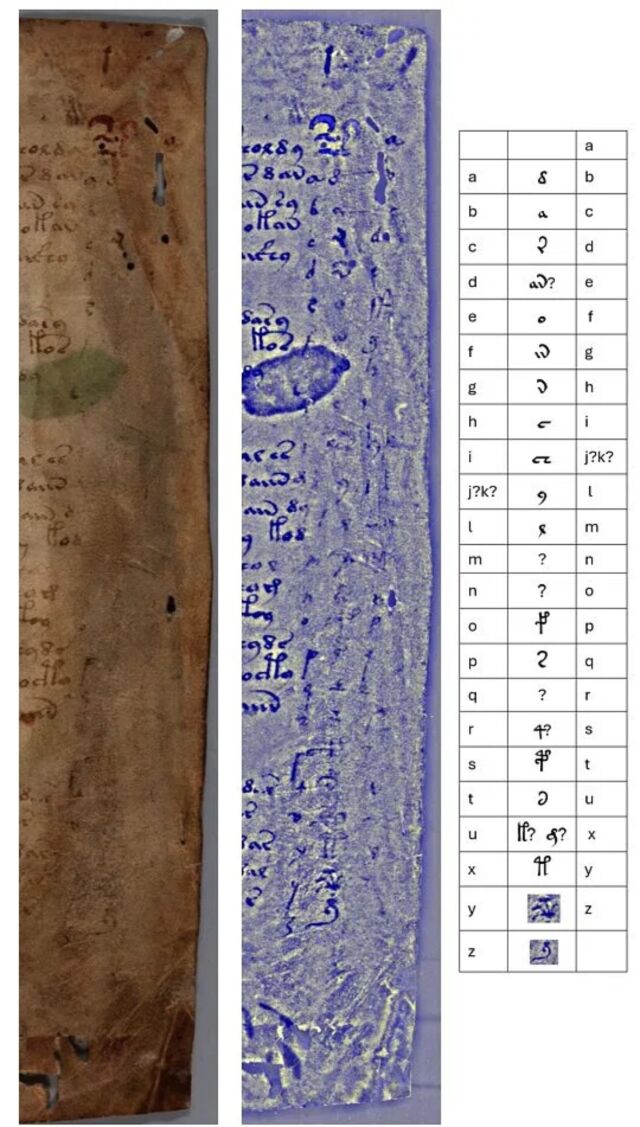

About 10 years ago, several folios of the mysterious Voynich manuscript were scanned using multispectral imaging. Lisa Fagin Davis, executive director of the Medieval Academy of America, has analyzed those scans and just posted the results, along with a downloadable set of images, to her blog, Manuscript Road Trip. Among the chief findings: Three columns of lettering have been added to the opening folio that could be an early attempt to decode the script. And while questions have long swirled about whether the manuscript is authentic or a clever forgery, Fagin Davis concluded that it’s unlikely to be a forgery and is a genuine medieval document.

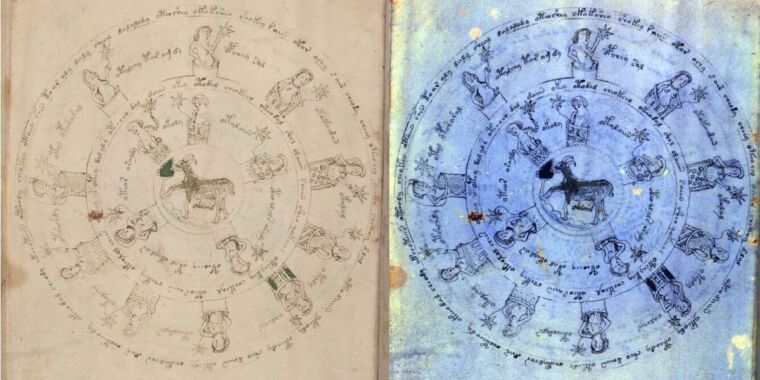

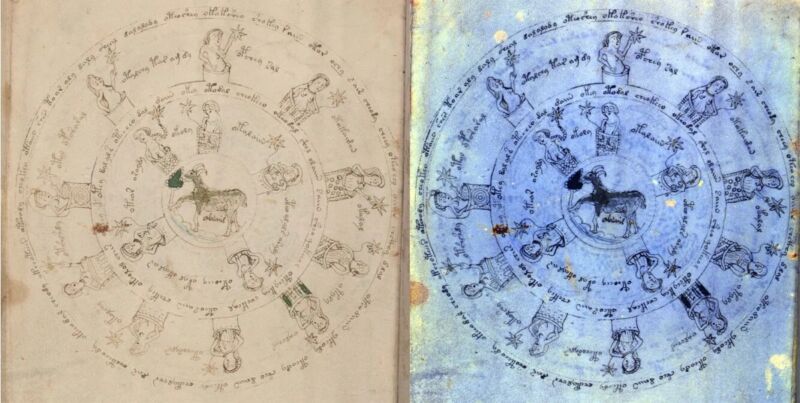

As we’ve previously reported, the Voynich manuscript is a 15th century medieval handwritten text dated between 1404 and 1438, purchased in 1912 by a Polish book dealer and antiquarian named Wilfrid Voynich (hence its moniker). Along with the strange handwriting in an unknown language or code, the book is heavily illustrated with bizarre pictures of alien plants, naked women, strange objects, and zodiac symbols. It’s currently kept at Yale University’s Beinecke Library of rare books and manuscripts. Possible authors include Roger Bacon, Elizabethan astrologer/alchemist John Dee, or even Voynich himself, possibly as a hoax.

There are so many competing theories about what the Voynich manuscript is—most likely a compendium of herbal remedies and astrological readings, based on the bits reliably decoded thus far—and so many claims to have deciphered the text, that it’s practically its own subfield of medieval studies. Both professional and amateur cryptographers (including codebreakers in both World Wars) have pored over the text, hoping to crack the puzzle.

Among the most dubious is a 2017 claim by a history researcher and television writer named Nicholas Gibbs, who published a long article in the Times Literary Supplement about how he had cracked the code. Gibbs claimed that he had figured out that the Voynich Manuscript was a women’s health manual whose odd script was actually just a bunch of Latin abbreviations describing medicinal recipes. He provided two lines of translation from the text to “prove” his point. Unfortunately, said the experts, his analysis was a mix of stuff we already knew and stuff he couldn’t possibly prove.

Fagin Davis was among Gibbs’ most vocal critics. She also did not mince words when critiquing the 2019 claims of Gerard Cheshire, an honorary research associate at the University of Bristol, when he announced his own solution. Cheshire claimed the mysterious writing was a “calligraphic proto-Romance” language, and he thought the manuscript was put together by a Dominican nun as a reference source on behalf of Maria of Castile, queen of Aragon. “Sorry, folks, ‘proto-Romance language’ is not a thing,” Fagin Davis tweeted at the time. “This is just more aspirational, circular, self-fulfilling nonsense.” Two days after the initial announcement of Cheshire’s “breakthrough,” the University of Bristol released a statement retracting its original press release.

Multispectral secrets revealed

Lisa Fagin Davis

Per Fagin Davis, in 2014, the Beinecke Library granted permission to the imaging team from The Lazarus Project to take multispectral images of ten pages from the Voynich manuscript with the intent of making them publicly available online. For various reasons, the images weren’t posted. A few weeks ago, Fagin Davis emailed Lazarus Project member Roger Easton of the Rochester Institute of Technology asking if she could examine the images, and he agreed.

Multispectral imaging is useful for analyzing things like delicate medieval manuscripts because it can reveal faded or overwritten text, among other insights. Different substances reflect and absorb specific frequencies of light differently. For instance, medieval inks had a lot of iron in them, so the ink would penetrate the parchment surface more deeply. So even when the ink was scraped away or faded over time, its molecular bonds remained, and those traces fluoresce under UV light. The imaging technique has already been used to examine the Archimedes Palimpsest, among other artifacts.